Forks in The Road

LITERARY WORK

The Road is a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel by Cormac McCarthy published in 2006 and adapted as a movie three years later. The Road is an uncomplicated story featuring a small cast of characters but the challenges they face are larger than life.

PLOT

The setting: A familiar North American landscape shortly after an ecological collapse triggered by war, likely. Almost all living things are gone; crops, animals, people. Our heroes are an ailing father and his ten-year-old-ish son.

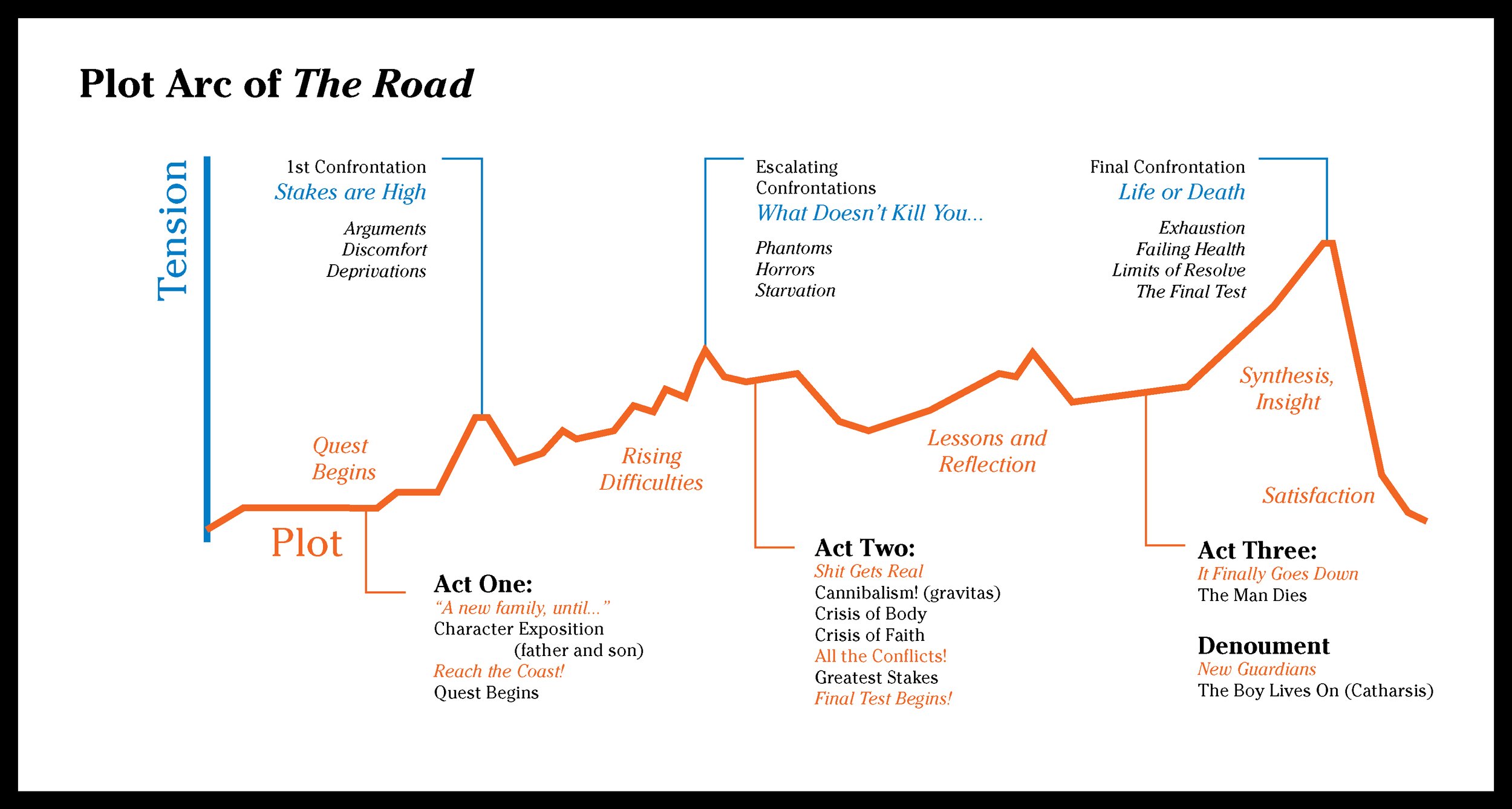

The heroic pair embark on a dangerous quest to find civilization and, with it, refuge from the environmental hazards and protection from the pervasive violence scavenging the world around them. Along the way they encounter obstacles that test their minds, bodies, and spirits, but through perseverance and commitment to their ideals, they reach their goal and the boy’s life is saved.

The story is set in a familiar post-apocalyptic setting but carries within it deeper explorations of the limits of compassion and empathy, care and love, against the “everything” that conspires to crush it. Against a growing certainty of failure, we watch the man struggle to keep his young son alive. Throughout the story, the man has his precautions and instincts proved inadequate, and he must draw on his waning reserve of hope to keep going. His health is in decline and he will die well before his son is old enough and strong enough to fend for himself.

The sadness is amplified by the bleak setting. The world is without hope, and so it is the boy that comes to represent our collective future and be a steward of humanity's goodness. McCarthy’s prose can be expansive and in both the book and its movie adaptation, it is the boy’s innocence that seems to represent all innocence, his life in the future is our life in the future… and, of course, we root for him and his protective father to survive. This is the story of The Road.

Exposition: We are introduced to the man and boy as they are already into their quest to reach a distant and undefined coast. Through flashbacks (in the movie), and memories (in the book), we learn of a global cataclysm that has recently destroyed almost all life on the planet.

The setting is explained through flashbacks and memories. Characters introduced during the course of the story, survivors, are mostly obstacles to the heroes though they all provide unexpected lessons that prove useful later.

Rising Action: The threats stack up in The Road starting with the hostile environment. Dead trees fall over without warning. There are earthquakes and fires and dust and ash everywhere, and at night it is raining and freezing.

As events unfold we learn about threats coming from other desperate survivors. One of humanity’s oldest taboos, cannibalism, is rampant. Most people are dead and gone, so only the most resourceful and unscrupulous people remain. The land is truly lawless, but not in a fantastical “Mad Max” way… it’s bleak, there are no people, there is only ruin and death.

Throughout the heroes’ experiences, we readers are led to question the futility of their enterprise… death comes easily in this place and surely is hostile enough to erase either of the main characters. They are cold and exposed to the elements. They are starving and have little food. The man’s health is failing. They lose all of their possessions. They are constantly hunted by people with ill intent. The man contemplates euthanizing his son then taking his own life but he only has one bullet. It becomes clear that there is no salvation at the end of their quest. The world will likely die. The stakes are high.

Climax: The pair reach their destination and it yields nothing. By this point in their bleak enterprise, they don’t have any hope left to feel despair. They are merely disappointed. The fact that the “big reveal” is not even depressing helps illustrate the utter lack of hope they maintain. They are exhausted and have faced every challenge imaginable. The man has been in failing health for weeks and then is shot by an arrow; the final straw, so to speak.

The man dies, leaving the boy alone on a desolate gray beach. The boy will certainly die of exposure and starvation in time. From a distance a figure approaches. It is not a cannibal; it is a good-hearted man, a new guardian.

Falling Action: The boy is rescued by a company of kind-hearted survivors.

Denouement: The boy will live with the new company and carry with him the memories of his father.

The principal driver for the story is the heroes’ quest for safety and comfort. Its antithesis is a violent and ravenous dying world.

Peter Whitley

Professor Opal Johnson

Research Paper: The Road

15 July 2022

AUTHOR, DIRECTOR, SCREENWRITER

The Road is Cormac McCarthy’s 10th novel and earned him a Pulitzer Prize in 2007. McCarthy is also the recipient of the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award. His work includes four novels that were famously adapted to screenplays; The Road starring Viggo Mortensen (adapted in 2009), No Country for Old Men starring Tommy Lee Jones (2007), Child of God starring James Franco (2013), and All the Pretty Horses starring Matt Damon (2000). His movies are box-office hits. McCarthy has also written screenplays like The Counselor starring Michael Fassbender (2013).

McCarthy frequently explores somber themes about resilience and faith against outsized evil or indifference. His writing style is often sparse and direct, leaning more on diction and rhythm than decoration to shape the nuances of the characters and the environments they navigate.

The Road’s screenwriter, Joe Penhall, has lots of experience spinning a yarn. He has written for a variety of mediums; television, stage, and screen. His credits include the series Mindhunter (2017–19), The Road (2009), and a television movie Blue/Orange (2005), and more.

The Road’s director, John Hillcoat, is known for his gritty cinematic treatments showing tough, dirty men surviving against all odds. His credits include a Run-the-Jewels music video (2021), an episode of Netflix’s Black Mirror (2017), and the movies Lawless (2012), The Road (2009), and (the excellent) The Proposition (2005), and so much more. Much of Hillcoat’s cinematic career features musician or band biographies.

CONTRAST AND FINDINGS

The novel offers a lot to interpret. The heroes encounter all kinds of challenges that are difficult for complex and nuanced reasons. Some of these challenges are overt and play well to the big screen. The cinematic scenes of survival in a hostile environment are energetic and offer lots of visual action; chases and confrontations. In the movie these action scenes seem to punctuate each challenge succinctly, and the movie has a familiar rhythm of action and reflection, like rolling waves. In the novel, the action sequences augment the psychological tension and philosophical conflict that the man is struggling with. For example, the man would rather kill the boy quickly and humanely than let him fall into the hands of people that would torture him, or to die of starvation and exposure alone in the wilderness, and so throughout the story he grapples with the probability that he will soon be required to euthanize his own son. That struggle is limited to a scene or two in the movie.

The movie and novel do not vary much in tone or plot but there are a few noteworthy differences. The movie stays true to the plot of the book and so no new scenes or characters are introduced. About a dozen scenes and characters from the book were omitted from the movie. Some of these omissions make sense; their removal merely abbreviated the story. Some of the omissions are due to practical reasons; to keep a reasonable length, that they could merge information through the movie’s wider sensory band (like music and cinematic effect).

Both the movie and the book are successful in similar kinds of ways but the book, I feel, is the more elegant and accomplished expression of the story. Most of the differences between the two are due to the affordances of the mediums. The movie carries sound and pictures and provides definition where, in the book, there is only a description of what is seen and heard. What we cannot see or hear, however, are the thoughts that flow freely through the written tale. In the movie, these subtleties are conveyed through the excellent acting by Viggo Mortensen, the man, and Cody Smit-McPhee, the boy, and through cinematic opportunities like voice-over narration. We don’t need to explicitly hear what someone is thinking on the screen because actors can express much of it through their faces and actions. It’s hard to compare the efficacy of those two very different forms of emotional expression. It’s fair to question whether the written word is better suited to express a complex emotional state than a performance with a music score. Maybe sometimes it is and sometimes it isn’t.

There are several scenes in the book that are omitted in the film, or are handled so differently as to be unrecognizable. In the book, for example, the pair encounter a person suffering horrible burns all over their body. The burned person is going to die from their injuries and there is nothing to be done. This early encounter in the book establishes that the pair do not have resources to provide help to anyone, and that there is nothing to do in the face of cataclysmic injury. This scene was omitted from the movie probably because most of what the scene established could be accomplished in other scenes.

In another instance a passage from the novel was deemed too repulsive to convey on screen. The book features brief depictions of cannibalism and there is a sequence involving an infant child that was too graphic for visual storytelling. The scene is an important escalating encounter and so it was revised to something show a woman and her son running from a small group of bad-intentioned men in the distance. The movie’s adaptation was not as shocking as the related encounter in the novel.

Much of McCarthy’s poetic diction is lost in the cinematic experience because the story cannot pause and allow the viewers to think on a word or to grab their dictionaries, but also because the pictures are doing more of the storytelling work and they don’t need definitions (in the same way that words do).

Some of McCarthy’s art is eclipsed by the panoramic impact of the scenes, drowned-out by a soundtrack, or up-staged by a cinematic treatment (like a camera view). People don’t speak the way McCormack writes, (though he’s excellent at naturalistic dialog), and that makes the writing artistry lost in the movie version of the tale. I found this is true for his other movie adaptations as well; the nuanced novels sometimes are made flat by the adaptation. In The Road, the movie threatens to draw us into an adventure caper, for example. The novel is expansive in its inquiry whereas the movie is hopelessly tethered to its action sequences. McCarthy’s novels are not traditional adventure stories but they become more so when they are adapted for the screen.

The movie can do things the book cannot, like using cinematographic techniques to enhance tension or convey information to the viewer. This is mostly effective and efficient cinematic storytelling, but it sometimes falls flat. In one instance the camera approaches the sleeping boy with a handheld point-of-view angle that most movie-goers will intuitively associate with “the killer’s point-of-view.” This viewpoint never occurs in the book and ends up cheapening the cinematic experience by cheapening and distorting the story’s original point-of-view. It was a bit tawdry. Thankfully these are exceptions in the movie.

CRITICISM

The pairing of a hardened survivor tasked with protecting an innocent child is a familiar theme. McCarthy is a master at creating adventurous stories with life-or-death consequences that usually have plenty of both. In The Road we watch the a man struggle with the burden of protecting an innocent and vulnerable child from the violence of the world. In this novel we see McCarthy interpret this popular and recurring theme. There are plenty of other examples of this motif from around the world. “Man-and-child against the world” was the centerpiece of the best-selling manga from the 1970s, Lone Wolf and Cub, as well as the premise behind movies like Leon The Professional and even the recent Star Wars spin-off, The Mandalorian. The Road is better than those, though, because it embraces the deepest, most difficult aspects of the hero’s struggle. The Road makes The Guardian’s top-ten Father-Son stories of all time.

It is difficult to point to the story’s shortcomings in a specific sense because the book is so impactful as it is. Cormac McCarthy has a lovely and uncommon writing style that eschews punctuation marks and leans often on obscure words and elegant comparisons to paint the picture.

One challenge may be that McCarthy’s diction often invokes the right word even when it is obscure. After looking up yet another unfamiliar word, I found that not only is the word exactly right for the story in the definitive sense, but the word also brings its phonetic poetry to the rhythm of McCarthy’s prose. His word choice is impeccable and I suppose that’s largely what great writers do; they choose words good well. It can be distracting to be reaching for the dictionary in the middle of a story even when the payoff is always worth it.

CONCLUSION

There’s little doubt that The Road is one of my favorite books. The movie is good, but the novel is a masterwork that has left its mark on me in lots of ways. Not only are its emotional touchstones powerful and moving, but McCarthy’s writing is itself inspiring and innovative. Taken together, The Road is the literary treasure that happens to make for a pretty good movie.

Cormac McCarthy has two new books being released near the end of 2022 that I’m looking forward to. I have three or four of his books and have enjoyed them all for their evocative and direct writing style as well as the rousing stories of fortitude.